jens ullrich

.jpg)

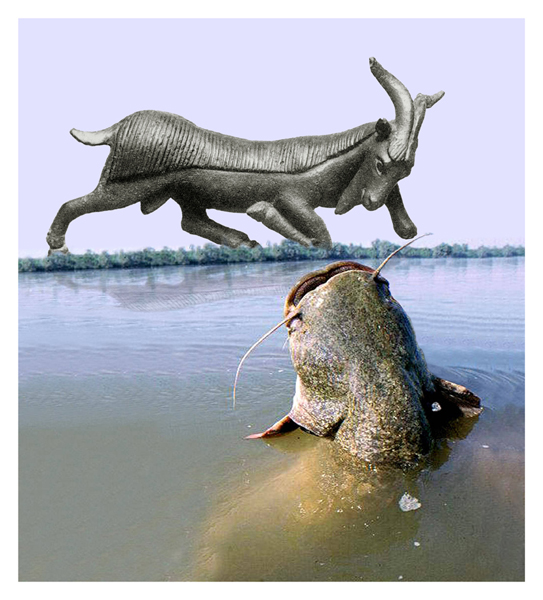

Jens Ullrich: twosome assemblies 018 (Pech-Merle), 2007

Jens Ullrich: twosome assemblies 006 (Karagwe), 2007

Jens Ullrich: twosome assemblies 028 (15th century), 2007

Jens Ullrich: twosome assemblies 036 (6th century A.D.), 2007

twosome assemblies

Photomontages in sculptured wooden frames of size between 42 x 42 and 58 x 42 cm.

Animal and Image

“In logical/theoretical thinking, the animal and the picture are considered to be different entities, with the likeness of the depiction being a factor in the relationship between the two. However, this differentiation is not present in magical thinking – animal and picture are one. The magical qualities of the picture are equally applicable to the animal. In logical/ conceptual thinking, the magical qualities of the picture are not the logical cause of the animal’s death. But in magical thinking, the killing in the picture – the drawing of the arrow – is the same as killing the animal. This is the nature of parallelism and unity. Humans can be animals, pictures can be animals. Posited here is a tangible oneness and real singularity, not a symbolic meaning.

Another important factor in this kind of magical thinking is the absence of the concepts of time and space. In the logical thinking of Kant, space and time are those principles of empirical knowledge which – as prerequisities for the possibility of experience – are prerequisites for the possibility of the objects of experience. Space is an essential precondition of reality in order for external perception to be possible. This is not the case with magical thinking. When the conjuror fires an arrow – an arrow that is supposed to kill an animal hundreds of miles away – the concept of space is nullified. Through this magical act, the two locations that form the arena for this act are merged into one. All spatial barriers are destroyed and a unity of objects is established. It is exactly the same with perceptions of the concept of time. As with space, time merges with the visual objects to form a unified whole.

Not only does the arrow that was fired for magical purposes have an impact in a completely different place, but the impact also occurs at a completely different time. This merging, this unity joins together two topics of thought that are unconnected in conceptual thinking.

The opposition within unity also applies to the notion of death. The dead are the alter ago of the living in the same way that the picture is the alter ego of the animal. A division between the symbolic and the real, between meaning and existence, between soul and body has not yet occured. The deceased move to another land where they continue to exist. They live there with body and soul, unseparated from their previous bodily existence. The dead and the living are a whole, a unity. (…)

These are the characteristics of magical thinking – the thinking of primeval times. Even today, all of us carry this type of thinking within ourselves. It lives in the substrata, in the unconscious, in what is felt. The writing is on the wall, as we still say today. Surviving within such words and phrases is the original layer of early thinking, magical thinking.”

Herbert Kühn: Vorgeschichte der Menschheit (Prehistory of Man), Cologne: DuMont Schauberg 1962, p. 110–111.

twosome assembly – press text for the exhibition in Berlin 2009

Seeing the death of an animal – or rather seeing a dead animal – intensifies the sense of one’s own aliveness and yet it can still be unbearable because it always involves a confrontation with the transience of life in general. Pictures of dead animals – as have been produced for millennia – are pictures of absence within substance. Death itself remains invisible and intangible. The dead body serves as a metaphor for death. The series of collages on show at reception were made using images of dead animals that Jens Ullrich found on the internet. Most of images are photographs taken by hunters or anglers of their prizes. In many of these trophy photographs, there is a clear attempt to present the animals as if they were asleep. The violent nature of their death is frequently concealed – the bloody wound on the polar bear is covered with snow; the hunter holds the head of the slain leopard as though it were still alive; the angler cradles the dead catfish in his arms as if straining to momentarily prevent the animal’s rigorous movements. This oscillation between wanting to prove that the animal is actually dead while simultaneously not being able to bear the fact that its death was brutal and violent – this is what makes these images so powerful. Jens Ullrich has removed the people and their triumphant poses from the photographs. Instead he has given each animal another animal for company. The loneliness of the dead animal is thus overcome by a togetherness with an artistic animal depiction. These sculptures and drawings from all different epochs of art and cultural history appear like guardians or custodians of the dead animals to which they have been allocated. Whether in the form of cave paintings, the tribal and folk art of various regions and eras, or the more abstract animal sculptures of the 20th century – the focus is always on creating an impression of vitality, on reaching an artistic understanding of an animal’s essence as expressed in its poise and movement. While the artists worked to make lifeless materials appear alive, the hunters and anglers try to manipulate the animal they have killed so that it still appears alive for the photograph. In both cases, the intensity is strongest in the transitional area between alive and dead. The goal is to capture life, to understand the essence of the animal and to approach the unfathomable nature of death. When viewing the pictures, one experiences the intimate moment in which the soul (or life itself ?) flows back and forth between the animal’s body and the artistic representation. The transience of life finds a place of shelter in the materiality and symbolic power of the artistic animal depictions.

Jens Ullrich (* 1968 in Tukuju/Tanzania) studied at the Academy in Düsseldorf. Works as an artist in Berlin and runs the exhibition space “Center-Berlin”.